The Map of Hierarchy and a Case of Autism

by Amy Rothenberg ND, published in Naturopathic Doctors News & Review September 2011

After 25 years of practice, I find myself increasingly interested in how to follow a patient over time. Is it enough to see a patient once or a few times? How do we fair as a profession in terms of long term follow up? What about treating children into adulthood? With regard to homeopathy in particular, are there any guideposts that let us know our patient is moving in the right direction? Certain philosophical and practical tools can be helpful. This article, through a pediatric case presentation, describes one such tool, the Map of Hierarchy*.

One of the things I have most loved about practice is the long arc of treating a baby or small child and watching them develop over time. In many ways this has mirrored my own evolution as a mother, first of little ones and now of three college-aged kids. It should be that with good naturopathic care and homeopathic prescribing, a person reaches their optimal level of health, that somehow their genetic potential has more of a chance of being realized. We all like the overnight miracles, the patient who makes great strides in a few short months either from a brilliant prescription or more commonly from a joint effort of doctor and patient and the healing power of nature. But with children, things can be both easier and more difficult. Lifestyle changes may or may not be relevant, compliance may or may not be forthcoming and in the case of autistic patients, some of the challenges seem insurmountable. In this patient narrative, I focus on the use of the Map of Hierarchy, as opposed to case analysis or the elucidation of materia medica, as it has wide application for pediatric cases but also is relevant for all patients.

Perhaps more than any group, those on the autistic spectrum give us the chance to observe how homeopathy impacts a patient over time and it is an area in practice where we can all use guidance in terms of long term follow-up care.

Meet Charlie

Little Charlie was a four-year-old towhead locked away in a world of his own when he first presented in the office. With no language skills to speak of, no self-help abilities and seemingly no interest interfacing with the world around him, his parents arrived at my clinic feeling desperate. They had implemented the DAN protocol; they had committed a small fortune and endless hours to an in-home ABA program, on top of a state-of-the-art, early intervention and top-notch preschool program. Unlike other children on the spectrum, Charlie seemed nearly unresponsive and made very little progress in the year since his diagnosis.

The first thing I noticed about Charlie was how strikingly beautiful he was, with wide and light blue eyes, porcelain skin and long, lush eyelashes. He made no eye contact with anyone in the room that day and wore only a far away look on his face. He had no history of seizure activity and had not sustained a head injury. His hearing and vision were intact. Early in my practice, patients like Charlie made me anxious and worried; what could I possibly do to help? But in the ensuing years, I have seen autistic children come running back into this world when they were once so remote. I have seen school-aged kids begin to talk when they had long been silent and I have seen violent, destructive children settle down and move toward the essential tasks of learning and relating to both objects and people. Every autistic child is different, though there are often shared symptoms. For the homeopath, it is in the forest of varied presentations that we find the symptoms and particular characteristics upon which to prescribe.

Charlie seemed 100% nonresponsive to sound and to touch. He sat in a lump most of the day as people did things with and for him. That said, he was a robust looking child and did eat whatever was put in front of him, without relish and with only a few food preferences.

His mother’s pregnancy, her third, had been uneventful with prenatal vitamins taken several months before conception, early and consistent prenatal care, and a natural childbirth. Her two daughters were alive and well. He was a perfect baby his mother recalls, except he did not nurse like his older siblings. He never got the hang of it and the family decided early on to use formula.

I never like hearing the phrase “perfect baby,” which, at least in this case, was defined as never crying, sleeping through the night and taking several long naps each day. It’s not right. Babies should cry, should be demanding at least on occasion, should make their physical and emotional needs known. Many kids who are diagnosed with autistic spectrum disorders will have a history of being quite difficult, colicky and restless, but a subset, likely related to homeopathic constitutional type, will be remembered as Charlie was: “perfect.”

He never seemed to make eye contact and his parents became worried by around 6 months. He did not seem interested in his older sisters and did not smile. Their pediatrician brushed aside parental concern saying that all kids bloom on their own schedule. To my ears, if a mother of three thinks there’s a problem, there usually is! It is known now that the earlier interventions take place, the better it is for any child on the spectrum. As the rise in autism incidence occurs, all parents and the doctors who care for families will be trained in observing and addressing early signs of autistic spectrum disorders.

Charlie had always been chubby with a big belly and poor tone, especially in his upper body. The main food he seemed to love was eggs and would eat them prepared in any way. He had a large head and sweat freely, top to bottom. He was chronically constipated, not yet toilet trained, having a bowel movement perhaps once or twice a week. His parents had tried gluten and casein free diets, good quality probiotics and many of the suggestions from their DAN doctor. He often had a runny nose and seemed worse during hay fever season with regard to congestion.

When most homeopaths hear big fat kid, sweaty head, chronic runny nose, constipation, desires eggs, they think, ahah! Must be a patient who needs Calcarea carbonica! But here’s where the error is made and why.

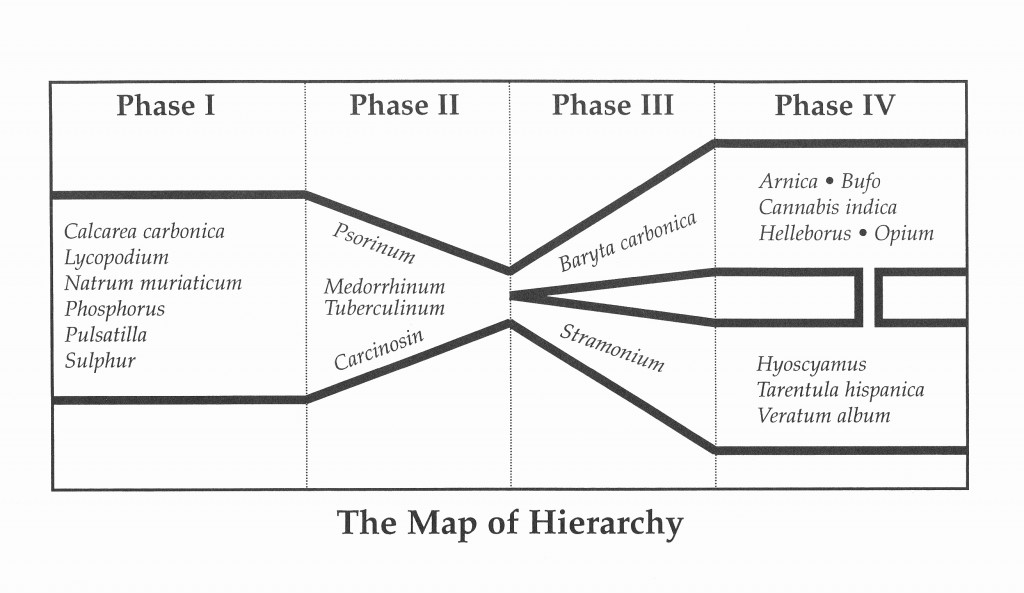

Take a look at the Map of Hierarchy, below:

Of course this is not a complete Map; there are many more remedies included. Paul Herscu ND, my husband and partner, conceived this Map many years ago and we have taught hundreds of homeopaths to think along these lines. The remedies to the left represent common remedies, ones we give often to all sorts of people with all sorts of complaints, but those who are basically oriented to the world, mentally and emotionally in more typical ranges.

Of course this is not a complete Map; there are many more remedies included. Paul Herscu ND, my husband and partner, conceived this Map many years ago and we have taught hundreds of homeopaths to think along these lines. The remedies to the left represent common remedies, ones we give often to all sorts of people with all sorts of complaints, but those who are basically oriented to the world, mentally and emotionally in more typical ranges.

We can see a person needing Natrum muriaticum who is depressed or a person needing the remedy Phosphorus who is anxious, but the level and intensity of emotional and mental issues is generally worse as we move toward the right on this Map. As we move to the right, we can see remedies that address deeper pathology. But to the point of Charlie’s case: all of the remedies to the right will retain symptoms of remedies to the left. For example: if I have a patient who needs a remedy like Veratrum album, perhaps they are a bit manic, self absorbed, filled with ideas, a bit crazed, suffering with ulcerative colitis. As they get better, healthier, more balanced, we can see that they move toward the left of this map, perhaps needing a remedy like Medorrhinum. And over time, perhaps years, as they become more and more healthy, they may need a remedy like Sulphur. As we take a patient over time, if they start out all the way on the right, you would expect them to move toward the left. More on this a bit further on.

It’s also important in homeopathy, and probably all of medicine, to focus treatments on that which is most limiting to the patient at the time. So the fact that Charlie was chubby, craved eggs and was sweaty, was not really the point. The point was that he was totally unengaged, nonverbal and not doing the things a child must do that both reflect and add to development and growth.

The Right Remedy

Charlie’s history of severe constipation and his total detachment, perhaps best exemplified by the additional fact that he did not respond much to pain, brought to mind only a handful of homeopathic remedies. I needed a remedy that was unresponsive, slow in movements, constipated and incommunicado. Opium and Helleborus topped my list. I gave him Opium 200c that first visit with hopes that we could bring Charlie out of his world and into ours.

I made sure to spend adequate time with his parents, talking about what I had seen that remedy do with other similar patients and preparing them. Using the Map of Hierarchy, I knew that the right direction for Charlie was for him to move to the left on this map and that likely, the next remedy he would need would, the next phase he would go through, would include some challenging behaviors. But I figured, in Charlie’s case, it was better that he be unpleasant, than not there at all.

Indeed, at our two-month follow up, Charlie came in and was clearly different. He was running around like he had a train to catch, over and over he picked up blocks and put them in the bucket, dumped them out and started again. He ran back and forth to his mother with blocks. Still no eye contact, no language, no real self-help skills. But he had woken up, he had come into the world and had begun to interact, mostly with the materials around him, strongly preferring objects to people. He was positively obsessed with whatever he was doing, going over and over and over again to whatever caught his eye. He was doing some stimming, holding the object du joura bit out in front of him and twisting his wrist this way and that. His parents were torn, on the one hand they knew this was the right direction, on the other, he was much more difficult to control. I personally, was elated! Charlie was waking up! I also knew from experience that all the treatments and supportive approaches they had tried to no avail in the past, would now be much more effective. I encouraged them to carry on in their efforts with diet and with behavioral approaches with renewed hope and dedication.

Moving Along the Map

In the course of that year, Charlie had 3 doses of Opium in ascending potency and then one day at an office visit, it became clear that he needed a different remedy. Although he was five now, his behaviors were closer to a 2 or 3 year old. Of course they were! He’d never done any of those things before, parallel play, repeating questions, annoying his sisters. His speech had come along, with a big vocabulary, His accuracy with pronouns was poor, he often spoke in lines from favorite videos and songs, he did not initiate dialogue. But he could name objects and get across basic bodily needs and some rudiments of emotional expression.

Charlie also started to get sick more. He seemed to catch every cold his sisters brought home, unlike his earlier years. With each infection he developed swollen submaxillary glands that held on even when he was no longer ill. His repetitive actions, his childish ways (in homeopathic repertory language, we use “childish” to describe behavior that is less mature than expected for the age of patient,) along with his chronically swollen glands pointed me to the remedy Baryta carbonica, and I was happy to see him moving, albeit slowly, toward the left on the Map of Hierarchy. I gave this remedy hoping it would help him to be less hyperfocused and more relational. I also knew that if a child enters into the world—from an isolated autistic state– at the age of 4 or 5 or 6, that often they have a serious deficit in their ability to relate to others and to be socially appropriate. I often have to remind parents that any steps into the world are good, that behavior issues that arise, we can work with.

And Charlie gave us many to work with, from pushing and grabbing to hitting and biting. His one-on-one aid at school had a singular purpose: to help Charlie learn to keep his hands to himself. As he came out of his shell, he seemed to have a lot of needs and they could not be met fast enough. His sixth year was spent working firstly on his growing ability to talk, rather than use physical urges to get what he wanted and secondly, to toilet train. He managed to graduate from kindergarten that year, well on his way to both goals.

We had a hiatus of two years without a visit, due to other issues in the family, so when I saw Charlie, a big 8 year old who bounded into my office and gave me a big hug, I was happy and a little overwhelmed by his exuberance. In the intervening years we had worked long distance, through a colleague and I had continued to recommend the Baryta carbonica, but it was clear he no longer needed that remedy. He had continued to move to the left on the Map of Hierarchy as though he had spread the Map out on his lap and decided where to go.

Ongoing Social Changes

Now he was about to begin the third grade, a strong reader and capable math student. He was still socially awkward, did not pick up on all the social cues and had personal space issues, often standing too close or coming in too fast to another person’s space. But he was loving and gregarious, helpful, and able to do most of the things you’d expect from an eight year old: dress and feed himself, put his laundry in a basket, complete basic homework assignments with support and follow along in an age appropriate movie or story book. He still hyper-focused on various subject areas, but now seemed to fit the word “quirky” more than any other. He was fascinated by trucks and building equipment, like many kids, and had become adept at Legos. His seasonal allergies had become year round, making his mother wonder if perhaps it was allergy to dust or cat dander. He was basically healthy, still robust looking. He was no longer violent in any way, no longer got the acute infections that had plagued him a few years back and seemed much more typical in affect. He was still a hot kid, was very thirsty and messy to the hilt. Any room he played in looked like a tornado had just whipped by. I asked if he still loved his eggs and he looked at his mom, his mom looked at him and they both shook their heads with a resounding NO! Somewhere along the line, along that Map of Hierarchy, he’d lost that desire. At this point, what seemed to limit him most were two things: his exuberance, actually a lovely quality, that needed to be tempered to an appropriate expression for the setting and his ongoing social challenges.

The Right Decision

In a warm and thirsty kid who is messy, thirsty and dislikes eggs, most homeopaths would correctly prescribe Sulphur.

Charlie has taken Sulphur a few times a year over the past two years, when his allergies are kicked up or when he hits a social bump in the road. I expect he will need this and closely related remedies for a long time to come and look forward to treating him in the coming years. I imagine that teen years, with their onslaught of hormones will be a particularly challenging time for him. I look forward to treating him into adulthood and supporting his and his family’s efforts.

Being privy to the lives of our patients, caring for a patient or a family over years and decades is one of the greatest rewards of being a doctor. With a simple tool like the Map of Hierarchy, which reflects a philosophical understanding, we can see that we are moving in the right direction with a patient. In treating those with complex pathology or overlapping diagnoses, it is helpful to have some guideposts along the way.

* The Map of Hierarchy, was first delineated in Dr. Paul Herscu’s book Stramonium with an Introduction to Analysis Using Cycles and Segments. New England School of Homeopathy Press 1996.